Aifric Mac Aodha is berne yn Dublin yn 1979. Hja studearre Aldiersk en modern Iersk oan de universiteit fan Dublin. Har earste bondel, Gabháil Syrinx, kaam út yn 2010. Hja hat lesjûn yn Sint Petersburch, New York en Kanada en kolleezjes Aldiersk en modern Iersk jûn oan de universiteit fan Dublin. Hja wennet yn Dublin dêr’t se no wurket foar An Gúm, in útjouwer yn de Ierske taal. Hja is redakteur yn de Ierske taal fan it tydskrift The Stinging Fly. Aifric hat ferline jier the Oireachtas Prize for Poetry wûn. Foreign News is Aifric’s nijste bondel, dy’t ferline jier útjûn is troch The Gallery Press. Yn de bondel stean Ierske gedichten, mei in oersetting yn it Ingelsk troch David Wheatley. Hja ferbliuwt fan heal juny oant begjin augustus yn Ljouwert yn it ramt fan it útwikselingsprojekt Oare Wurden/Other Words.

Aifric: “I’m going to write a sequence of poems about the Frisian horse.”

How do you like it so far yn Ljouwert/Fryslân?

‘I like it very much although it took me a while to establish a rhythm. I needed to get my bearings before I could make headway, I think.’

What is your writing plan for Other Words?

‘I plan to finish a sequence of poems about the Frisian horse. The Frisian horse was a work horse, he was a war horse and now he’s used for dressage. I think that minority languages go through some, if not all, of those phases. I’m feeling my way in, at the moment, but I’m certain my time here – my time outside time – will stand to me. I also met a lovely artist who is creating a Frisian horse, using peat. I hope to include a poem about her work in the sequence. The poems will be published on the Other Words website and will hopefully be translated to the five languages involved in the project.’

Do you have contacts here in the city?

‘I do, yes. I’m in regular contact with Marre Sloots who works at Tresoar and is our woman from Ljouwert. She met me on my first night and we had dinner with André Looijenga, an Other Words alumnus. Another day we visited the Tresoar archives and met with Bert Looper, the director. He gave myself and Helena Foṡnjar, a participant from Slovenia, an impressive tour of the archives. He also presented us with a copy of a beautifully produced book about the history of the Frisian language (As long as the tree blooms). The book mentions the earliest examples of Frisian are found in the form of glosses – something else we can relate to.’

What are your plans for sightseeing?

‘I’ve been busy. I climbed the Oldehove tower and I attended the Escher exhibition early on. It was very cleverly done. I also went to the Natuurmuseum where a group of young boys were watching a taxidermist plunge and stuff an owl. I sat down on one of the stools beside them and tried to follow what the ‘guide’ was saying. That was very interesting… I’d never seen a taxidermist at work. And of course, everything is especially strange when you’re abroad.

There’s a Basque evening on at the Livingroom of Languages soon and more showcased languages, thanks to Mirjam Vellinga… so my evenings will be full too. Meeting new people is very much part of the tourist experience here. I met Karen Bies, for example. She’s staying in Ireland now on an Other Words exchange. Karen is spending the summer in a beautiful part of Ireland called Belmullet, in County Mayo, and I think she plans to go to Galway too. As it happens, Galway will be the 2020 cultural capital of Europe.’

I read that you taught in St Petersburg, New York and Canada.

‘In New York and Canada, I taught language classes to adult learners of Irish descent. In St Petersburg I had general students of linguistics, who were passionate about the Celtic languages. I had fifteen students or so, from Monday to Friday, nine to five. I’ve never met students like them. They just knew everything.’

Did you speak Irish from home?

‘Not exactly – it’s more complicated than that. My father spoke fluent Irish and he was very committed to the Irish language. He was born in Belfast, and learned Irish every Summer in the Donegal Gaeltacht (an Irish-speaking area in Ireland). He fell in love with Irish from the age of five and learned the language inside out. In his spare time, he translated poetry into Irish from Portuguese, Spanish and Greek . And he did everything in his power to promote Irish throughout his professional career. He was a geography professor and because he was working in Galway, in the West of Ireland, where there is a strong Gaeltacht, he would give many of his geography courses in both English and Irish. I often think of that dedication, of the fact that he was willing to double his own workload when he could [and should] have been writing more poetry himself.

My mother had very good Irish but I think I would have to say that English was our first language at home. As a family, we are happy to speak Irish together at Irish language events and we sometimes speak Irish amongst ourselves, but on the whole, I think we’re more ourselves in English. It pains me to admit it, but I think it’s true. That said, I’m lucky enough to work for an Irish language publisher and I have plenty of friends I can’t imagine communicating with in English.’

You learned Irish writing in school?

‘I went to an all-Irish school where every subject was taught through Irish. And my University degree was in Old and Modern Irish.’

Who are your favorite Irish writers?

‘I have some old favorites and some new ones. The writer Liam Ó Muirthile is very much in our hearts, at the moment. His recent death is a terrible loss. There was nothing he couldn’t say and what he had to say was always worth hearing. Our first three modernists, Seán Ó Ríordáin, Máire Mhac an tSaoi and Máirtín Ó Direáin continue to matter to us all. And of the up-and-comers, Máirtín Coilféir is my favourite.’

Are those poets an inspiration to you?

‘I would say so. Certainly, yes, they’re in my blood and bones.’

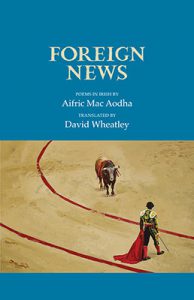

What can you tell about the title of your last book, Foreign News? Why did you choose that title?

‘A lot of the poems in the book were written abroad. As Irish speakers, even now, we battle to make the point that Irish doesn’t belong by the fireside, that it’s as international as the next island language. So perhaps I was being a little tongue in cheek. There is a poem called ‘Foreign News’ in the collection but it wouldn’t be my favourite, by any means.’

Do you know David Wheatley, the translator of the book, in person?

‘Not terribly well, I suppose, although we’re in regular contact by e-mail and I’m a huge fan of his own work. When my first book came out, he was learning Irish with another poet, Justin Quinn, in Donegal and they had a copy of Gabháil Syrinx. In the evenings, they started translating the poems together. Later Chicago Poetry Magazine brought out a special edition on Young Irish Poets. David translated some of my poems for that. Peter Fallon, my publisher (The Gallery Press) liked those translations and he sped things along.’

What can you tell about the title of your first book, Gabháil Syrinx, which means: The Taking of Syrinx?

‘I was hiding behind a myth, the way young poets often do. The first three poems in the collection are about the Greek tale of Pan and Syrinx. Pan falls in love with Syrinx and Syrinx escapes Pan by being turned into a wavering reed. The story fitted my life at the time and I liked the fact that the word ‘gabháil’ has more than one echo/meaning in Irish.’

In your last book there’s a poem about Segovia in Spain. Did you visit that place?

‘I did. Sometimes a change of scene brings on a poem. It unblocks you, it’s a shot in the arm. That certainly happened in Segovia. It’s a remarkable place. Myself and my fiancé had gone to Madrid for a wedding and we decided that we would travel on to Segovia for a few days. When I came home, the lines came in stops and starts but I knew I’d see a long poem through, eventually.’

You used to be a teacher in Dublin, but you are an editor now.

‘Yes, I used to lecture. After that, I started working as a translator with the new English-Irish dictionary and from there, I got a job with the Irish publishing house, An Gúm. I sometimes miss teaching but I think that as a lecturer, you’re never off the hook… and if I’m honest, I never felt like I had what it takes. I’m too thinly read and I give up too easily; I’m missing the brains and the temperament for that life. At least with editing, things are a little more clearcut. There are deadlines and books to finish. We publish textbooks, children’s books and translations of classics like Peter Pan and Dracula. The work is varied and I couldn’t have kinder or wiser colleagues.’

Aifric thús yn Dublin

Last year you won the Oireachtas Prize for Poetry. Are you a wellknown Irish writer now?

‘I don’t think any of us would or could describe ourselves as well known. Writers have moments in the sun, if they’re lucky. This feels a bit like mine. I’ve had a busy year and I’ll be reading at more festivals in the months to come, including The Edinburgh Book Festival and The Franco-Irish Literary Festival. Much more importantly and with many thanks to Orlagh Ní Raghallaigh from Ireland and the Other Words project, I’m fortunate enough to be here in Ljouwert with time on my hands.’